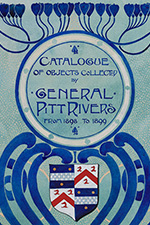

Catalogue of the Pitt Rivers collection of antiquities and ethnographical material

The catalogues offer significant insights into the very wide interests of Pitt-Rivers, and form an important document in the history of collecting ... It is above all the meticulous execution of the illustrations which ... guarantee them a place in the history of archaeological illustration’" Michael Thompson and Colin Renfrew

The catalogue of the Pitt Rivers collection consists of nine volumes containing all the information usually found in a museum catalogue, such as date of acquisition, provenance, and cost of purchase. However, what makes them special is that they also contain beautiful hand painted illustrations of a remarkable ethnographic collection of objects and artefacts collected by Augustus Pitt Rivers.

Image: Examples of the hand painted illustrations.

Augustus Henry Lane Fox was born in Yorkshire in 1827, the son of an army officer. He spent a short period at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, before joining the Grenadier Guards, initially as a lieutenant, in 1845. In 1850 Lane Fox became involved in the testing of rifled weapons, and he would go on to become an instructor at the School of Musketry in Kent. He briefly saw military action in the Crimea before being passed unfit for active service and returning to training and testing duties. Lane Fox remained in the army, though often free of military duties, until he retired with the rank of lieutenant-general in 1882.

Lane Fox’s professional interest in the rifle and its development led him to collect historic firearms, soon expanding his collection to include a wide range of ethnographic materials. First obtaining objects and artefacts during his overseas postings, and also from friends and family, Lane Fox would soon start to purchase objects from all parts of the globe at auction houses and from specialist dealers. He initially collected out of personal interest, but then began to see his collection as educational. The publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859 had a marked effect on Lane Fox's thinking, and he began to develop a theory of the evolution of culture, using his ethnographic collection to illustrate the idea of typology; the realization that objects can be placed in chronological sequence on the basis of slight changes in design. To this end he collected everyday objects and artifacts, rather than works of art. In a paper published in 1875, he wrote that ‘the collection ... has been collected during upwards of twenty years, not for the purpose of surprising anyone, ... but solely with a view to instruction. For this purpose, ordinary and typical specimens, rather than rare objects, have been selected and arranged in sequence.’ In the 1860s Pitt Rivers became interested in archaeology and he worked in the field in Ireland, Yorkshire and the South Downs and also in Egypt whilst on holiday there. His archaeological finds, added to his collection, would further feed into his theory of cultural evolution.

In the 1870s, wishing to allow greater access to his collection, Lane Fox lent a large part of it to the Bethnal Green branch of the South Kensington Museum. This would later be moved to South Kensington, and then be donated to Oxford University in the early 1880s where it would form the basis for the Pitt Rivers Museum.

In 1880 he inherited the estates of his cousin Horace Pitt, 6th Baron Rivers. This not only led to a name change, he now became Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers, and a move to Dorset, it also made him a very wealthy man and he was able to concentrate on his archaeological and ethnographical activities. Though his previous collecting outlay had not been insignificant, money was now no object, and Pitt Rivers began building up a second collection which he would display at his private museum in Farnham. He also was able to employ staff to help with his archaeological fieldwork and also secretarial and curatorial staff to manage his collections. This meant that Pitt-Rivers could institute formal cataloguing of his purchases, recording information such as date of acquisition, description and provenance information. The catalogue would also include illustrations of each item. To this end museum assistants were employed for their artistic ability and they would go on to produce the nine large and beautifully illustrated volumes between 1884 and Pitt Rivers’ death in 1900. Pitt-Rivers was very clear about the skills his assistants required, the most important being draughtsmanship, and Pitt Rivers took an active role in assessing the artists he would employ. The number of artists who worked on the catalogues is unknown, though it is at least five. Relatively little is known about them, other than they mostly had a Royal College of Arts training. What is without doubt though, is that the catalogues constitute a remarkable and beautifully illustrated record of a remarkable collection and a tribute to the man who created it and the artists who created the illustrations with such skill and draughtsmanship.